Twenty years ago, as a young woman and freshly-minted Peace Corps volunteer, I was likely, on a January morning, swathed in layers of clothing and clutching a hot cup of water to keep myself warm. I taught English at a college in southwest China, somewhere on the road to Tibet, at a school lodged neatly between a city of one million and the iconic rural countryside. In one direction, down an unpaved and decidedly bumpy road, was the city of Mianyang, with high-rise apartment buildings, taxis careening around corners, and grocery stores with escalators. In the other direction, down a dirt path littered with trash and traversed by free-range animals and fruit-sellers who still used an abacus, was the countryside, gently rolling hills covered in fields and dotted with the homes of villagers who held tight to China’s agrarian history.

I saw, firsthand, the juxtaposition between modern China, with shrink-wrapped chicken breasts and Diet Coke for sale, and the traditional village lifestyle, sans indoor plumbing or refrigerators.

The college was a meet-in-the-middle world where the young Chinese population prepared for jobs in cities, teaching in schools for better pay than many of my students’ parents made as farmers, many of them barely scraping together enough money to send a child off for schooling at all.

As I sat between the two worlds, I observed many differences between my American culture and that of China. One of the greatest differences, to my mind, was the treatment of the elderly in China compared with my experiences in America. In the Chinese countryside, and even in the cities, the elderly were respected and treated with dignity I didn’t see in America. Perhaps part of that was simply that I didn’t see as many elderly in America at all, as so many Americans 65+ lived in assisted living facilities rather than among family. In fact, as I watched the Chinese elderly walk throughout the campus and the streets of the city, I realized that none of my friends back home had a grandparent living in the home with the family, and in my own family, all of my grandparents lived in assisted living facilities and retirement homes. I noticed how often I saw Chinese grandparents walking slowly with a toddler, sauntering through a city park or down a country road, keeping pace with the child rather than the American way, the child keeping pace with the adult. I saw grandparents carrying babies on their backs in baskets far more often than mothers carrying babies, and in my apartment complex, it was commonplace to see a grandmother holding her grandchild a few inches above the ground, whistling softly to cue the child to pee. Potty training in a land without diapers was a revelation to my American eyes.

I began to understand the family dynamics of my Chinese counterparts as I settled in, and with many visits to villages with my students, I saw a lifestyle foreign to me. I saw three generations (sometimes four) living together, caring for each other, fighting with each other, and generally depending on each other, a social safety net based on giving and take that was far more relational and personal than anything I’d seen back home. I was, on the one hand, compelled and taken with this seemingly natural, connected way of life, and I was also slightly uncomfortable with the thought of embarking on such a familial journey with my own relatives.

I loved watching Chinese grandparents, children, and grandchildren sitting around the family table for meals, caring for each other, and often sleeping together.

I didn’t know, however, if I could see that in my own future, my parents whipping up dinner and running after my children while I put in a few more hours at work or did the food shopping. It all seemed, well, a little close for my American sensibilities, and I realized that my sense of independence (so ingrained in my cultural fabric) was based in large part on my separation from my parents rather than my connection to them or dependence on them. As a child, I was taught to take care of myself, and the thought of helping my parents was not only uncomfortable to me but also, it turns out, to my parents, who said they would feel weak and demoralized to need care from their children.

Thus, the pros and cons of each of our culture came to light as I remained in China for my two-year Peace Corps stint and kept in touch with several students and friends over the years. In general, I saw a great deal of respect for the elderly in China, based on the Confucian principle of filial piety, a virtue fostered and cultivated, denoting love and respect for one’s parents and ancestors. My Chinese students, for example, returned home during any vacation or school break to help their parents with farming or simply to spend time with them. There was never a sense of dread in this journey; rather, my students were eager to see their parents, return to their villages, and eat the foods they missed at school. One student came to my office one day quite excited. She’d just received her first paycheck as an English tutor. She was shaking (literally) with happiness that she would be able to purchase her father’s favorite liquor and take it home to him that coming weekend. The love and adoration often went both ways, of course. When I spent a summer with a Chinese family in the town of Panzhihua, the mother and aunt always plucked out the biggest, juiciest pieces of meat for their son, ensuring he ate as much as possible to keep him healthy and strong.

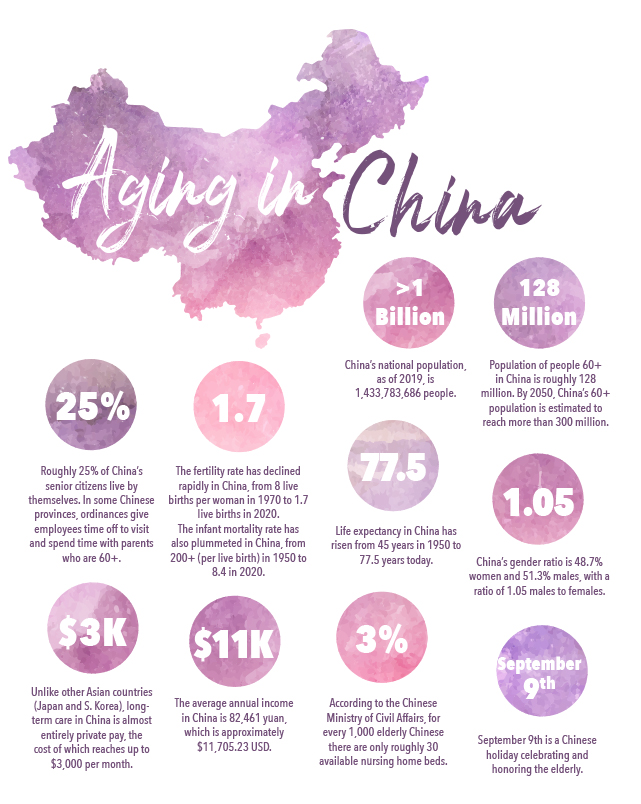

When I embarked on the idea of aging around the world, I immediately thought back to those memories from my Chinese experience and planned to write a heart-warming article on the multi-generational family dynamic in China, how families all live together, supporting one another and caring for each other, the young and old, the old and young. As I began my research, however, a different reality came to light. In the wake of dramatic economic development and as a result of the effects of the one-child policy (OCP) – instituted in 1979 to curb China’s rapidly growing population – the traditional family dynamics I saw as commonplace in China twenty years ago have changed, and in some ways, particularly regarding China’s aging and senior population, the changes have been stressful and uncertain.

Traditionally, a Chinese senior depended on his or her family for care in the second half of life. What I saw as a Peace Corps volunteer reflected this tradition. Parents invested all of their time, energy, and financial support in their children with the expectation that the children would, in turn, care for the parents in their senior years. Often, the parents cooked, cleaned, and cared for their grandchildren as part of this arrangement, thus enabling their children to go out and work freely in cities or on family farms. With economic development, however, many of China’s young adults are lured to jobs in cities, migrating far from home in search of better job opportunities, education, and independence. Many of these children send remittances home, but even that can be precarious in large cities where expenses are high, jobs can be scarce and social security is all but non-existent.

As the younger population migrates, the older population remains in villages and smaller towns, often caring for the grandchildren or simply left alone to care for themselves. As one interviewee said in Zhang and Goza’s article titled “Who Will Care for the Elderly in China,” published in the Journal of Aging Studies in April of 2006, “…the young are now migrating to urban centers to work cheaply as manual laborers. Those left behind in the countryside are the old, the weak, the sick, and the disabled.”

Even if children send money home for the care of their parents, the seniors are quick to point out that money cannot care for a person’s emotions or replace family connections.

As China’s economic development has moved at break-neck speed, the cultural traditions and norms have struggled to keep pace. In the recent few decades, many migrants remained in urban areas rather than making money and returning to villages or hometowns. They met and married spouses had children, and continued working in jobs unavailable to them in the countryside. This meant parents and grandparents had to depend on themselves or neighbors and community members for assistance, defying the traditional pattern of family life so entrenched in Chinese culture. As the internet expands, there has been a slow reversal of this trend, and some migrants are returning to villages to launch new lives as entrepreneurs; however, this reverse migration is relatively new and precarious, leaving many Chinese seniors alone in villages or rural communities while their children struggle for a better future in the cities. In 2016 alone, nearly 300 million rural Chinese migrated to cities.

China’s one-child policy (OCP) has also created social consequences, many of which are faced by its aging population. Traditionally, Chinese families have been large and birth rates high. In 1970, for example, the birthrate was 8 live births per woman. Today, the birthrate is 1.7 live births per woman. With fewer children, Chinese parents have fewer options for family care in their senior years. Traditionally, children shared the responsibility of caring for parents. Parents might engage in what is called ‘living by turns,’ where the parent lives with different children for periods of time. Several of my Chinese friends, for example, bring parents to live with them once they have children of their own. In this way, Chinese parents are useful to their children and grandchildren and are also cared for as they age. Another arrangement, much more common today as western influence and ideas of independence grow in popularity, is the ‘living close but separately’ plan, where parents live alone but close to children. The child (or children) can care for the parents but also live independently of each other. This is growing increasingly popular among urban Chinese residents, who have the financial and community support to sustain two households. In families with siblings, one sibling might care for the parents and/or live with the parents, and the other siblings would contribute financially to both the parents and the sibling providing care. With the OCP, an only-child must provide all of the financial, physical, and emotional support him or herself. Chinese seniors, many of whom are in the ‘sandwich generation’ with their own parents to care for, do not want to put the burden of this care on their children and feel the pressure has become too great for their one child. Zhang and Goza write, “The general conclusion was that no one should count on his or her only child as their sole insurance against old age. They also indicated that as parents of a single child they would still invest most of their resources in this child and expect little, if anything, in return.”

Without the security of the traditional family structure, and as options and western ideas develop within Chinese culture, the Chinese government, communities, and individuals are becoming creative, industrious and determined to solve the issue of who will care for China’s aging population as it explodes in the coming decades.

In the 1990s, insurance policies became available (mostly through private funding) for the parents of one child families. These policies include support for elderly parents of one child, safety insurance for an only child, and insurance for couples with no children at all. Most who can afford such policies reside in urban areas, and many rural residents are still unaware such policies exist or do not have the income to purchase them. In addition to insurance policies, communities are responding to the needs of seniors by creating neighborhood committees made up of local citizens to provide assistance for older residents including activities, educational resources, and safety patrols. Protestant churches also provide these services in the community, including nursing homes and health clinics.

Many seniors, having watched the incredible economic transitions of the past 40 years, wonder: what will our society look like in another 10 or 20 years? What can we expect?

All of this cultural transition, however, is not bad. There is also a sense of independence for many seniors who are able to choose their retirement style, which might include spending the second half of life in a community designed to meet their needs, full of other seniors, planned activities, and a slower pace of life. Rather than depending on their children, who are struggling with China’s new economy and the pressures of providing for their own children, retirees can live separately from their children but nearby, providing help when needed but not living alongside family, which can be stressful and tiresome. My own best friend, a Chinese woman named Cindy, lives exactly this lifestyle, a merging of the traditional culture and modern reality. Cindy’s parents live in the same apartment complex she, her husband, and her daughter live in, and her parents are able to visit with their grandchild daily and help out but not feel burdened or overwhelmed with responsibility.

“I want my parents to relax after giving me so much during my childhood. I don’t want them to keep working,” Cindy says. “I have hired a nanny for our daughter, but my parents are also close by so we can all help each other.”

As we chat on her sofa so many years after my Peace Corps days, Cindy’s mother is in the kitchen peeling apples for a snack and making tea, lest we catch a cold in the damp winter afternoon. The apartment is comfortable, and the nanny has taken the baby for a bath. It’s not the lifestyle I saw twenty years ago, in the villages and hometowns of my students, but it’s an answer to the changes China faces in its new role on the world stage, changes that filter down through the fabric of society. What will it look like in another decade? We’ll all have to wait, cups of tea in hand, and see.